Mark Adriaenssens and his colleagues are looking for gold — and other precious materials — all in a quest to save the planet.

While thousands of delegates are debating how to best fight climate change at U.N. talks in Poland, experts are gathering up old electronic equipment from Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, helping to manage one of the fastest-growing waste streams in Europe.

European Union nations created 9 million tons of waste from devices like computers, televisions, fridges and cellphones in 2005. That figure is expected to grow to more than 12 million tons a year by 2020.

Waste from electrical and electronic equipment — known by its acronym WEEE — can contain heavy metals like mercury and lead, or flame retardants that are bad for human health and the environment.

The Out of Use company run by Adriaenssens works out of a warehouse-like facility in the northern Belgian town of Beringen. It dismantles computers, office equipment and other devices and recuperates an average of around 90 percent of the raw materials from electronic waste. Free pick up is offered.

The process is time consuming. Hazardous substances can be released during the dismantling and disposal of the electronics, which potentially poses health risks to workers.

After careful selection, Mark and his colleagues strip any non-reusable devices of all environmentally harmful substances before recycling them. That ensures that no harmful substances like oil, asbestos, lead acid batteries, toners and ink cartridges or mercury are released into the environment.

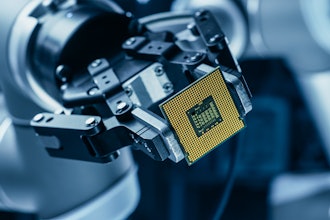

Then the devices are taken apart and processed for secondary raw materials, in line with EU laws on recycling WEEE.

This old electronic and electrical equipment can be a treasure trove for minerals, as the production of modern electronic equipment uses some of the world's scarcest and most expensive resources. Indeed, around 10 percent of total gold worldwide is used to make them.