"We did not actually plan this, but that is just how science works sometimes: you start researching one thing and end up somewhere else," says ETH Professor Dimos Poulikakos. Together with scientists from his group and from the National University of Singapore, they developed and tested various superhydrophobic materials - which are, like Teflon, extremely good at repelling liquids such as water and blood. The goal was to find coatings for devices that come into contact with blood, for example heart-lung machines or artificial heart devices.

One of the materials tested demonstrated some unexpected properties: not only did it repel blood, but it also aided the clotting process. Although this made the material unsuitable for use as a coating for blood pumps and related devices, the researchers quickly realised that it would work ideally as a bandage.

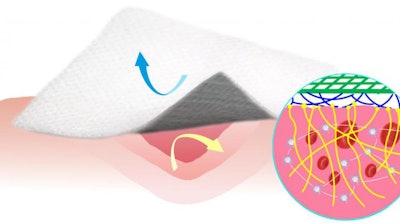

Repelling blood and achieving fast clotting are two different properties are both beneficial in bandages: blood-repellent bandages do not get soaked with blood and do not adhere to the wound, so they can be later removed easily, avoiding secondary bleeding. Substances and materials that promote clotting, on the other hand, are used in medicine to stop bleeding as quickly as possible. However, to date, no materials that simultaneously repel blood and also promote clotting have been available - this is the first time that scientists have managed to combine both these properties in one material.

Antibacterial effect

The researchers took a conventional cotton gauze and coated it with their new material - a mix of silicone and carbon nanofibres. They were able to show in laboratory tests that blood in contact with the coated gauze clotted in only a few minutes. Exactly why the new material triggers blood clotting is still unclear and requires further research, but the team suspects that it is due to the interaction with the carbon nanofibres.

They were also able to show that the coated gauze has an antibacterial effect, as bacteria have trouble adhering to its surface. In addition, animal tests with rats demonstrated the effectiveness of the new bandage.

Reducing the risk of infection

"With the new superhydrophobic material, we can avoid reopening the wound when changing the bandage," explains Athanasios Milionis, a postdoctoral researcher in Poulikakos's group. "Reopening wounds is a major problem," he continues, "primarily because of the risk of infection, including from dangerous hospital germs - a risk that is especially high when changing bandages."

The potential areas of application are huge: They range from emergency medicine and surgery for avoiding major blood loss, to plasters for use in the home and on the go.

ETH Zurich and the National University of Singapore have applied for a patent for the new material. In the meantime, the researchers need to refine and optimise the material before it can be used on humans. They also say they need to conduct further testing, first on larger animals and then on humans, to prove its effectiveness and harmlessness.