MEXICO CITY (AP) — The U.S. parent company of a Mexican factory said Tuesday it has agreed to measures to ensure a free labor vote amid a battle by workers to unseat an old-guard union.

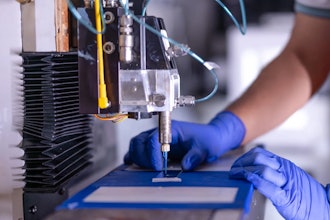

The Cardone company operates the Tridonex auto parts plant in Mexico’s border city of Matamoros, across from Brownsville, Texas.

The export facility was the subject of a complaint filed by labor unions in May under the U.S.-Mexico Canada free trade agreement, known as the USMCA. The complaint argued that new unions have been harassed and supporters fired for fighting corrupt old unions that have kept wages low in Mexico for decades.

Cardone said in a statement that it will work with Mexican authorities “to ensure a personal, free, and secret vote by employees” at the Tridonex plant.

The Philadelphia-based company pledged to inform “employees of their rights to collective bargaining and freedom of association and an absence of retaliation or discrimination if they exercise those rights.” It also said it will provide all workers with a copy of the current labor contract, something old-line unions in Mexico frequently don't allow employees to see. Cardone said it will also provide some additional compensation for some fired employees.

The independent union trying to organize the plant said it had not been consulted about the agreement. The outside organizer of that union, lawyer Susana Prieto, said, “We do not approve of the agreement.”

“The United States has reached an agreement with Tridonex without taking into account the working class, violating its rights,” Prieto said.

But she also said of the agreement: “We won. The first (labor) complaint is taking effect.”

The USMCA contains stronger labor guarantees than its predecessor, the NAFTA trade agreement. The USMCA allows a panel to determine whether Mexico is enforcing labor laws that allow workers to choose their union and vote on contracts and union leadership. If Mexico is found not to be enforcing its laws, sanctions could be invoked, including prohibiting some products from entering the United States.

Cardone said that under its agreement with the U.S. government, it "admits no fault or liability with respect to the matters raised in the petition and does not believe that a denial of workers’ rights has occurred at the facility.”

Supporters of the independent union said earlier this month that they had been harassed while trying to hand out leaflets by beefy representatives of the old-guard union. The group of mainly women handing out the leaflets said state police stood by and may have helped prevent them distributing literature outside the Tridonex plant starting in late July.

Video showed the independent union supporters handing literature to workers leaving the plant in their cars, when several stocky men in white shirts came out of the plant and tried to move them away.

For decades, corrupt Mexican unions signed low-wage “protection contracts” behind workers’ backs, often before plants were even opened. Union votes were held by show of hands, or not at all. Workers at many factories in Mexico were unaware they even had a union until they saw dues deducted from their paychecks.

Mexican workers make about 15% of wages for similar jobs in the United States.

As part of getting the USMCA approved. Mexico passed labor law reforms stating all union votes would be by secret ballot, and workers at all factories in Mexico could vote on whether to keep their current union.

But implementing those reforms has met resistance from old-guard unions affiliated with the Confederation of Mexican Workers, which once effectively served as an arm of the government to keep labor peace and wage rates low.

Jesús Mendoza, the leader of the CTM-affiliated union that currently controls the plant, depicted the independent union supporters as troublemakers.

“Let people work in peace, we want labor stability and recovery in Matamoros, they just cause trouble and scare off investment,” Mendoza told local media.