Repeated activity wears on soft robotic actuators, but these machine's moving parts need to be reliable and easily fixed. Now a team of researchers has a biosynthetic polymer, patterned after squid ring teeth, that is self-healing and biodegradable, creating a material not only good for actuators, but also for hazmat suits and other applications where tiny holes could cause a danger.

"Current self-healing materials have shortcomings that limit their practical application, such as low healing strength and long healing times (hours)," the researcher report in today's issue of Nature Materials.

The researchers produced high-strength synthetic proteins that mimic those found in nature. Like the creatures they are patterned on, the proteins can self-heal both minute and visible damage.

"Our goal is to create self-healing programmable materials with unprecedented control over their physical properties using synthetic biology," said Melik Demirel, professor of engineering science and mechanics and holder of the Lloyd and Dorothy Foehr Huck Chair in Biomimetic Materials.

Robotic machines from industrial robotic arms and prosthetic legs have joints that move and require a soft material that will accommodate this movement. So do ventilators and personal protective equipment of various kinds. But, all materials under continual repetitive motion develop tiny tears and cracks and eventually break. Using a self-healing material, the initial tiny defects are repairable before catastrophic failure ensues.

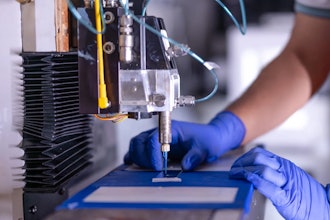

Demirel's team creates the self-healing polymer by using a series of DNA tandem repeats made up of amino acids produced by gene duplication. Tandem repeats are usually short series of molecules arranged to repeat themselves any number of times. The researchers manufacture the polymer in standard bacterial bioreactors.

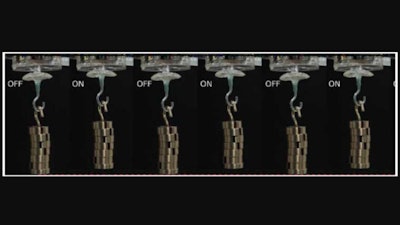

"We were able to reduce a typical 24-hour healing period to one second so our protein-based soft robots can now repair themselves immediately," said Abdon Pena-Francesch, lead author of the paper and a former doctoral student in Demirel's lab. "In nature, self-healing takes a long time. In this sense, our technology outsmarts nature."

The self-healing polymer heals with the application of water and heat, although Demirel said that it could also heal using light.

"If you cut this polymer in half, when it heals it gains back 100 percent of its strength," said Demirel.

Metin Sitti, director, Physical Intelligence Department at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems, Stuttgart, Germany, and his team, were working with the polymer, creating holes and healing them. They then created soft actuators that, through use, cracked and then healed in real time -- about one second.

"Self-repairing physically intelligent soft materials are essential for building robust and fault-tolerant soft robots and actuators in the near future," said Sitti.

By adjusting the number of tandem repeats, Demirel's team created a soft polymer that healed rapidly and retained its original strength, but they also created a polymer that is 100% biodegradable and 100% recyclable into the same, original polymer.

"We want to minimize the use of petroleum-based polymers for many reasons," said Demirel. "Sooner or later we will run out of petroleum and it is also polluting and causing global warming. We can't compete with the really inexpensive plastics. The only way to compete is to supply something the petroleum based polymers can't deliver and self-healing provides the performance needed."

Demirel explained that while many petroleum-based polymers can be recycled, they are recycled into something different. For example, polyester t-shirts can be recycled into bottles, but not into polyester fibers again.

Just as the squid the polymer mimics biodegrades in the ocean, the biomimetic polymer will biodegrade. With the addition of an acid like vinegar, the polymer will also recycle into a powder that is again manufacturable into the same, soft, self-healing polymer.

"This research illuminates the landscape of material properties that become accessible by going beyond proteins that exist in nature using synthetic biology approaches," said Stephanie McElhinny, biochemistry program manager, Army Research Office, an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command's Army Research Laboratory. "The rapid and high-strength self-healing of these synthetic proteins demonstrates the potential of this approach to deliver novel materials for future Army applications, such as personal protective equipment or flexible robots that could maneuver in confined spaces."