The path to peace in a trade war between the United States and China is getting harder to find as the world's two biggest economies pile ever more taxes on each other's products.

The United States is scheduled to slap tariffs on $200 billion in Chinese imports Monday, adding to the more than $50 billion worth that already face U.S. import taxes. China has vowed to counterpunch with tariffs on $60 billion in U.S. goods.

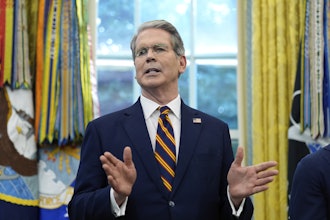

President Donald Trump is ready to up the ante, threatening to tax just about everything China ships to the United States.

"It's more likely than not that these tariffs will be put in place for a long time," said Timothy Keeler, a partner at the Mayer Brown law firm and former chief of staff at the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

The two countries are locked in combat over Washington's allegations that Beijing pilfers foreign trade secrets and forces U.S. companies to hand over technology in return for access to the Chinese market. The predatory practices, the U.S. says, are part of China's relentless drive to challenge American technological dominance.

The Americans and Chinese haven't held high-level talks since June, raising doubts about whether a resolution can be reached anytime soon.

"Both sides believe they can outlast the other, fearing any conciliatory move will be viewed as weakness and reduce negotiating leverage," said Wendy Cutler, a former U.S. trade negotiator who is a vice president at the Asia Society Policy Institute.

The tariff exchange is creating casualties in the United States. Companies that import Chinese materials and parts are facing higher prices. So are the consumers who buy everything from burglar alarms to baseball gloves. U.S. farmers are being hurt by China's retaliatory tariffs on soybeans and other agricultural products.

Some economists and trade analysts suspect that Trump has bigger goals than just getting China to change its aggressive high-tech industrial policies. The massive tariffs are raising costs — and uncertainty — for companies that rely on China for materials and components. Trump may be "trying to force U.S. companies to change their supply chains and reduce their reliance on China," said Robert Holleyman, a partner at the Crowell & Moring law firm and a former deputy U.S. trade representative.

Earlier, the Trump administration signaled that it might be willing to settle for a reduction in America's massive trade deficit with China, $336 billion last year. In May, in fact, it looked briefly as if Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Chinese Vice Premier Liu He had brokered a truce around a Chinese offer to buy enough American farm products and liquefied natural gas to put a dent in the trade gap.

But Trump quickly backed away. "He got a lot of criticism for being too soft on China," lawyer Keeler said.

The administration says its demands are clear: Stop stealing trade secrets. Stop coercing technology transfers. Stop favoring Chinese companies over U.S. and other foreign competitors.

But China's leaders have ambitious plans to turn their country from the world's low-cost manufacturer into a technological power in fields from robotics to quantum computing. They are likely to balk at meeting any U.S. demands that would slow the high-tech drive.

"Chinese companies don't have that type of technological sophistication," said Robert Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation think tank in Washington. "They know if they do it the organic way — by funding R&D and building up a university system — it's going to take 30 years. The Chinese don't want to wait that long."

In one high-profile example, the U.S. in 2014 charged five officers in China's People Liberation Army for computer hacking and economic espionage against six U.S. companies, including Westinghouse, U.S. Steel and Alcoa.

Even if the two countries reach a deal, it will take time for China to prove that it is living up to commitments to treat foreign companies more fairly, something the U.S. says Beijing has repeatedly promised and failed to do in the past.

"It isn't clear what steps China can show it is taking in the short-term to abandon its entire industrial strategy, which is ultimately a long-term process," Megan Greene, chief economist at Manulife Asset Management, wrote Wednesday.

China's leadership is in a difficult position, said Eswar Prasad, professor of trade policy at Cornell University.

"It has to cope with the economic fallout from the expanding trade war and try to limit the damage but has to be careful not be seen as caving in to U.S. demands," he said.

For now, the rising tensions, high stakes and tough underlying issues are making compromise elusive. Today's tariffs, said former U.S. trade official Holleyman, "may become the new normal."