Spacewalking cosmonauts set up an antenna for tracking birds on Earth and sent a series of tiny satellites flying from the International Space Station on Wednesday.

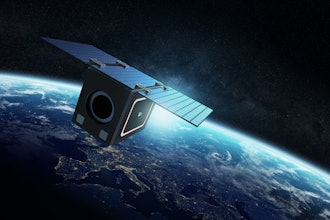

Russian Sergey Prokopyev used his gloved right hand to fling four research satellites into space. The first mini satellite safely tumbled away as the space station soared 250 miles above Illinois. By the time the fourth one was on its way 14 minutes later, the station was almost to Spain. Two were the size of a tissue box, while the other two were longer.

With that quickly behind them, Prokopyev and Oleg Artemyev spent the next several hours installing the antenna for a German-led, animal-tracking project known as Icarus , short for International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space. The cosmonauts had to unreel, drag and connect long, white cables in order to provide power and data to the system. At one point, Artemyev had to pull out a sharp knife to deal with a twisted cable.

"Can you give us some more difficult tasks please?" Artemyev joked as he routed the cables, a long and tedious chore.

A quick test verified the Icarus electrical connections. But the cosmonauts were running behind by this point, and their spacewalk ended up lasting nearly eight hours, longer than anticipated.

The space station is an ideal perch for the antenna, compared with a typical satellite, said project director Martin Wikelski of the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Germany. That's because spacewalkers could fix something if necessary and the computer is better protected from space radiation, he noted.

The project will start out tracking blackbirds and turtle doves already outfitted with small GPS tags, then move on to other songbirds, fruit bats and bigger wildlife.

Wikelski said researchers have ear tags for big mammals like gazelle, jaguars, camels and elephants, as well as leg-band tags for larger birds such as storks. The tags are easy to wear and should not bother the animals, he said.

Wikelski, who watched the spacewalk from Russian Mission Control outside Moscow, said researchers can better understand animal behavior through lifelong monitoring. Among the things to learn: where the animals migrate, and how they grow up and manage to survive.

"We also learn where, when and why they die," he explained in an email, "so we can protect our wild pets."

The space station is also home to three Americans and one German. They have two spacewalks next month.