The Environmental Protection Agency has completed one of its last major rollbacks under the Trump administration, changing how it considers evidence of harm from pollutants in a way that opponents say could cripple future public-health regulation.

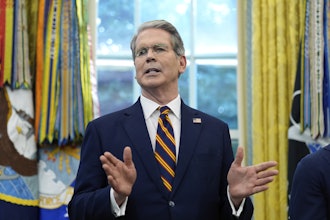

EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler is expected to formally announce completion of what he calls the “Strengthening Transparency in Regulatory Science” rule in an appearance before a conservative think tank on Tuesday. The EPA completed the final rule last week, but so far has declined to make the text public.

The new rule would require the release of raw data from public-health studies whose findings the EPA uses in determining the danger of an air pollutant, toxic chemical or other threat. Big public-health studies that studied the anonymized results of countless people have been instrumental in setting limits on toxic substances, including in some of the nation's most important clean-air protections.

Some industry and conservative groups have long pushed for what they called the transparency rule. Opponents say the aim was to handicap future regulation.

In an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal on Monday night, Wheeler said the change was in the interest of transparency.

“If the American people are to be regulated by interpretation of these scientific studies, they deserve to scrutinize the data as part of the scientific process and American self-government,” Wheeler wrote.

But critics say the new rule could force disclosure of the identities and details of individuals in public-health studies, jeopardizing medical confidentiality and future studies. Academics, scientists, universities, public health and medical officials, environmental groups and others have spoken out at public hearings and written to oppose the change.

“This really seems to be an attempt by Wheeler to permanently let major polluters trample on public health,” said Benjamin Levitan, a senior attorney with the Environmental Defense Fund advocacy group. “It ties the hands of future administrations in how they can protect the public health.”

The change could limit not only future public health protections, but “force the agency to revoke decades of clean air protections,” Chris Zarba, former head of the EPA’s Science Advisory Board, said in a statement.

Wheeler, in his Wall Street Journal piece, said the new limits wouldn’t compel the release of any personal data or “categorically” exclude any scientific work.

The EPA has been one of the most active agencies in carrying out President Donald Trump’s mandate to roll back regulations that conservative groups have identified as being unnecessary and burdensome to industry.

Many of the changes face court challenges and can be reversed by executive action or by lengthier bureaucratic process. But undoing them would take time and effort by the incoming Biden administration, which also has ambitious goals to fight climate-damaging fossil fuel emissions and lessen the impact of pollutants on lower-income and minority communities.