If you've ever opened an umbrella or set up a folding chair, you've used a deployable structure - an object that can transition from a compact state to an expanded one. You've probably noticed that such structures usually require rather complicated locking mechanisms to hold them in place. And, if you've ever tried to open an umbrella in the wind or fold a particularly persnickety folding chair, you know that today's deployable structures aren't always reliable or autonomous.

Now, a team of researchers from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have harnessed the domino effect to design deployable systems that expand quickly with a small push and are stable and locked into place after deployment.

The research is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

"Today, multi-stable structures are being used in a range of applications including reconfigurable architectures, medical devices, soft robots, and deployable solar panels for aerospace," said Ahmad Zareei, a postdoctoral fellow in Applied Mathematics at SEAS and first author of the paper. "Usually, to deploy these structures, you need a complicated actuation process but here, we use this simple domino effect to create a reliable deployment process."

Mechanically speaking, a domino effect occurs when a multi-stable building block (the domino) switches from its high-energy state (standing) to its low-energy state (laying down), in response to an external stimulus like the push of a finger. When the first domino is toppled, it transfers its energy to its neighbor, initiating a wave that sequentially switches all building blocks from high to low energy states.

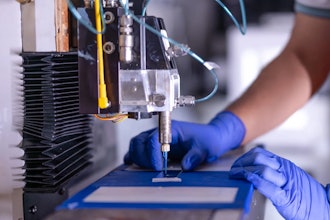

The researchers focused on a simple system of bistable joints linked by rigid bars. They first showed that by carefully designing the connections between the links, transition waves could propagate through the entire structure -- transforming the initial straight configuration to a curved one. Then, using these building blocks, the research team designed a deployable dome that could pop-up from flat with one small push.

"Being able to predict and program this kind of highly non-linear behavior opens up many opportunities and has the potential not only for morphing surfaces and reconfigurable devices but also for propulsion in soft robotics, mechanical logic, and controlled energy absorption," said Katia Bertoldi, the William and Ami Kuan Danoff Professor of Applied Mechanics at SEAS and senior author of the study.

Bertoldi's lab is also working on understanding and controlling transition waves in two-dimensional mechanical metamaterials. In a recent paper, also published in PNAS, the team demonstrated a 2D system in which they can control the direction, shape, and velocity of transition waves by changing the shape or stiffness of the building blocks and incorporating defects into the materials.

The researchers designed materials wherein the waves moved horizontally, vertically, diagonally, circularly, and even wiggled back and forth like a snake.

"Our work significantly increases the design space and functionality of metamaterials, and opens up a new pathway to control deformations within the material at desired locations and speed," said Ahmad Rafsanjani, a postdoctoral fellow at SEAS and co-first author of the paper.