Dubuque, Iowa (AP) — In the early stages of his career, Ted Schuster had the opportunity to take over a successful business in a massive urban market.

"I met an older blacksmith and he invited me to take over his business in downtown Chicago," Schuster recalled to the Telegraph Herald. "It was an established business and would have set me up just like that. But I didn't want to live in the city. So I took the chance on being able to get that kind of work here, and it paid off."

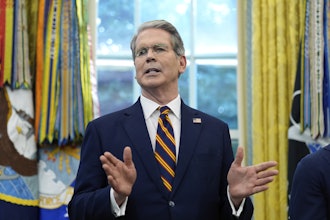

Shuster, now 56, has operated a blacksmithing operation, Prairie Forge, in eastern Iowa for three decades. The small-scale business is a far cry from the big-city environment its owner once considered.

To find Prairie Forge, a person must navigate a narrow, dirt road just off 310th Avenue near Hopkinton. The business is nestled within a nondescript property surrounded by thick timbers and tall grass.

Only the clangs of hammers against metal signal the presence of a high-end blacksmithing operation.

Prairie Forge creates a wide array of distinct furnishings, including chandeliers, dining tables, pedestals, candle-holders and other decorative pieces. Schuster said the majority of the products end up with well-to-do clients in the New York and Chicago markets.

Clients generally begin working with an interior designer or architect, who then contacts Schuster.

In some cases, these contractors present Prairie Forge with specific drawings. Other times, he plays a role in design.

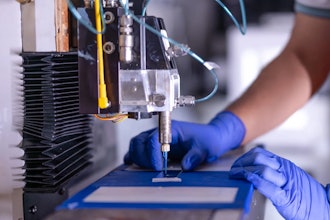

Schuster determines what materials he will need then cuts them to the proper length. He works with bronze, copper, mild steel, stainless steel and aluminum.

It's not an easy job, Shuster admitted.

"It is hot and loud," he said. "There is a risk of getting burned. I've taken many trips to the doctor's office. Thankfully, nothing that's been permanent."

Once the metals are selected and cut to size, they are heated to 2,200 degrees within a propane furnace or coal forge. The high temperatures make the rigid metals more pliable.

Schuster then uses a machine called a "power hammer" to texture and taper the pieces. The various parts are later pieced together through welding or riveting.

Pieces are then "finished" using a variety of potential products. The most common finish for Prairie Forge products is 22-carat gold, a flourish that underscores the sophisticated tastes of the business' clientele.

Previous generations of Schuster's family forged the path for his success.

He grew up on a farm in Iowa and drew inspiration from his grandfather, who owned a forge and schooled Schuster in the art of blacksmithing.

"When he visited, we would pull (the forge) out and make a chisel or a farm implement," Schuster recalled.

When his grandfather died in the 1980s, Schuster went to his auction and purchased that family forge, as well as some accompanying tools.

Initially, blacksmithing was a hobby. Schuster attended University of Northern Iowa and traveled much of the world. Wherever he traveled, however, he found a forge and took the time to keep improving his skills.

He began conducting his business in 1989. In 2000, Schuster commissioned the construction of a new building on the property. That building, which he helped construct, houses Prairie Forge today.

For more than half of his time in business, Schuster has been working alongside the same employee.

Josh Trenkamp began working at Prairie Forge shortly after graduating from high school. He credits Schuster for serving as a mentor.

"I was a snot-nose kid straight out of high school, just looking for a job," Trenkamp said with a chuckle. "I didn't know how to weld or anything. He taught me all that stuff. He taught me everything."

Prairie Forge once employed five workers. However, business slowed in the wake of the Great Recession.

Today, Trenkamp and Schuster are the only two people who work at Prairie Forge. Through the years, they have developed a "fluent" relationship, according to Trenkamp.

They know what each other is doing without needing to discuss it.

"We don't have to lean over each other's backs," he said. "We come in in the morning, start on a project and get things done."

Schuster believes there is more to a blacksmith than a skilled hand.

"You have to have an eye for design, for things like proportion and balance," he said. "Having an understanding of history helps as well."

Schuster said he benefited significantly from his time in college, where art and history were among his areas of focus. His education has helped him understand various architectural eras — and create pieces that mesh with a home's style.

As he moves into the later stages of his career, Schuster is hoping to shift into new product lines.

Namely, he is hoping to drum up business from local residents who want to memorialize loved ones. Schuster said he is available to meet with families, discuss design options and create pieces that would be displayed within one's home or beside a loved one's grave.

As Schuster enters the fourth decade of his blacksmithing career, he maintains a sense of optimism about the craft's future.

He noted that more women are entering the discipline and is heartened to see a new generation beginning to take up the mantle.

Schuster believes there are many components of being a blacksmith — the hands-on nature and the tangible results — that are right up the alley of today's young workers.

"I know millennials are oftentimes looking for an experience that is genuine," he said. "It doesn't get more genuine than heating up a hunk of iron and whacking it with a hammer. That is pretty real stuff."