Lax regulations, chronic short staffing and a law that muffled the voices of environmentalists on mining licenses made the devastating collapse of a dam in southeastern Brazil all but destined to happen, experts and legislators say.

The failure of the dam holding back iron ore mining waste on Jan. 25 unleashed an avalanche of mud that buried buildings and contaminated water downstream. At least 121 people have died, and another 226 people remain missing.

But one of the cruelest parts of the tragedy in Brumadinho is that it has happened before: In 2015, a mining dam burst about 80 miles (130 kilometers) away in Mariana, in what is considered Brazil's worst environmental disaster.

What's more, it could happen again, as many Brazilian states and the federal government move to ease regulation in the name of economic development.

In the three years since the Mariana rupture killed 19 people, the regulation of the industry has gotten less, not more, rigorous in Minas Gerais state.

"It felt like it was just a matter of time before something bigger would happen," said Josiele Rosa Silva Tomas, the president of the Brumadinho residents' association.

Problems that existed when the dams in Mariana burst, like dramatic short-staffing, have persisted, while a new law has reduced the say of environmental groups in the project licensing process.

And the danger remains widespread: A 2017 report from the National Water Agency classified more than 700 dams nationwide as at high risk of collapse, with high potential for causing damage.

In fact, some fear the risk may only increase. Environmental groups accused the previous Congress and president of rolling back significant protections, and many expect further weakening under President Jair Bolsonaro, who has said environmental regulation hamstrings several industries, including mining.

But the politics that contributed to the collapses in Minas Gerais are much more local. For centuries, the mineral-rich state has revolved around the mining industry — its name, given by Portuguese colonizers, translates to "General Mines."

More than 300 mines employ thousands in the state, often in poor, rural areas.

Civil society groups often struggle to achieve basic guarantees. For instance, Tomas' group has long fought to prevent mining projects from contaminating drinking water.

"Minas Gerais has a centuries-long history of being lenient with the mining sector. It's cultural," Joao Vitor Xavier, a state deputy, told The Associated Press. "The industry creates a discourse where they dangle jobs and economic growth in front of people, but they put profit over safety."

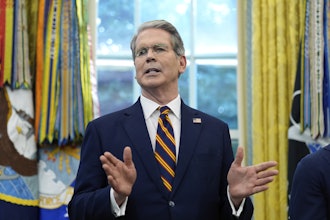

The CEO of Vale SA, which owned and operated the Brumadinho mining complex, acknowledges their regulatory measures fell short.

"Apparently to work under the (current) rules has not worked," Flavio Schvartsman said during a press conference several hours after the dam breach.

Vale officials have said they don't yet know why the dam collapsed.

Arrest warrants have been issued for five people responsible for safety assessments of the dam, including three Vale employees. Vale was also involved in the Mariana rupture: The dams there were administered by the Brazilian giant and Australia's BHP Billiton.

The Mariana collapse unleashed nearly 80 million cubic yards (60 million cubic meters) of mining waste into rivers and eventually the Atlantic Ocean. While its environmental impact is considered the worst in Brazilian history, Brumadinho has already far surpassed its death toll.

In the wake of the Mariana tragedy, Minas Gerais was already struggling to implement what regulation it had: A 2016 audit found the state had only 20 percent of the staff needed at the agency charged with regulating mines. Environmentalists say mining regulation has gotten even weaker since.

In 2015, the state approved a new process for licensing mining projects. It shifted responsibility from a board that included several environmental organizations to the state environmental secretary, who created a new board with a majority of participants favorable to mining industry interests.

Then-Gov. Fernando Pimentel argued the bill would reduce bureaucracy. But days before the law was approved, the Minas Association of Environmental Defense called it "one of the biggest setbacks in environmental regulation in the country."

"The conditions are set so the licenses never get turned down," Maria Teresa Corujo, a rare pro-environmental voice on the new board, told the AP.

In December, Corujo, of the National Forum of Civil Society in Watershed Communities, was the only member of the new board to vote against approving the expansion of the mining complex in Brumadinho. Notes from that meeting show the complex's pollutant rating had been downgraded — a move that is now the purview of the environmental secretary — allowing the company to skip regulatory steps.

In July 2018, Xavier, the state lawmaker who has pushed for a ban on iron ore waste dams, made a grave prediction.

"I'm not saying we might have other dam ruptures in Minas Gerais. I am saying that, from everything I've seen and studied, I have no doubt we will have more ruptures of dams," he told the state assembly.

Today, he still has no doubt that there will be more tragedies unless more rigorous regulations are implemented.

"These dams are not 100 percent safe," he said. "How many of them can rupture? Any one of them."