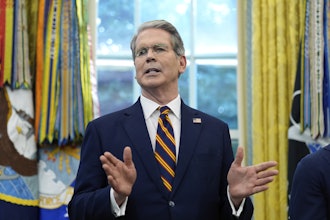

Sitting in his office beside photos of grandchildren decked in Philadelphia Flyers jerseys, Christopher Scott shakes his head. Another email has come in from another supplier. It wants to raise prices to cover the cost of President Donald Trump's tariffs.

For weeks, emails and letters have been arriving in a steady stream at Howard McCray, the small Philadelphia factory Scott runs with about 85 workers. It's mostly bad news. One supplier is charging more for shelving brackets, another for electrical switches, a third for wheeled castors. McCray needs those parts for the refrigerated display cases it produces for convenience stores and restaurants.

Since Trump imposed tariffs on imported steel and aluminum and on Chinese products, Scott, like many other American manufacturers, has had to rapidly switch gears.

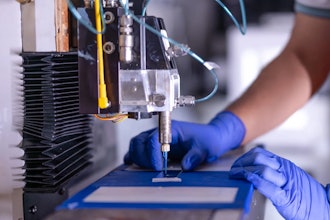

He had been optimistic about 2018, with plans for hiring and investment in new machinery. He had hoped, for example, to replace two 30-year old machines that cut holes in stainless steel sheets with a newer version that uses lasers and works twice as fast.

All that's now on hold. This year, McCray has slashed in half its spending on large equipment. Scott is also leaving four jobs unfilled and instead adding more overtime for his current staff.

"That's what the tariffs are doing to us," Scott, 59, said while giving a visitor a tour this month of the factory floor, straining to be heard above the pneumatic drills and hydraulic equipment. "We're just going to delay it until they come off."

Tax cuts that Trump pushed through Congress last year sharply reduced the tax burden on businesses. The administration argued that lower taxes would accelerate investment in machinery and high tech equipment. Over time, such capital spending tends to make workers more productive and speed the economy's growth. Yet Scott says that for his company, the higher tariffs — which are taxes on imports — have largely nullified any benefit from the tax cuts.

There is growing evidence that other companies are feeling similar strains. Business investment in large machinery and other equipment grew just 0.4 percent in the July-September quarter, the government said Friday. It was the slowest pace in nearly two years. And demand for computers, industrial equipment and other capital goods has dropped in the past two months.

"The prospect of a full-blown trade war with China and tariffs more generally are prompting some companies to delay investments for next year," noted Diane Swonk, an economist at Grant Thornton.

The tariffs have also injected a new layer of uncertainty into Scott's business. Right now, for instance, Scott is trying to decide what prices to quote for two potential customers he is pitching. Should he pass on to those customers the higher costs of the tariffs — or eat them, as he is doing now?

"If you price the tariffs in now, you risk losing the account," he says. "If you don't price them in, you risk losing money on the account."

The stated goal of the Trump administration's 25 percent tariffs on steel and 10 percent on aluminum, imposed June 1, was to limit cheap imports and spur hiring and growth in America's metals industries. In imposing the tariffs, Trump invoked national security: His reasoning was that low-priced imports hurt America's ability to produce items needed for national defense. Many critics have disputed that assertion.

Some companies have indeed benefited. Braidy Industries, an aluminum manufacturer, has broken ground on a plant in Kentucky that it says will create 600 jobs. U.S. Steel is spending $750 million on modernizing a factory in Gary, Indiana.

But across more industries, higher costs for businesses have begun spreading and leading economists to predict slower economic growth next year. And Trump has also imposed tariffs on roughly half the goods the U.S. imports from China.

3M Corp., for example, has said it's raised prices to offset the higher cost of goods subject to tariffs. Ford Motor Co. says the import taxes will raise its costs $1 billion through 2019. And Caterpillar says the steel tariffs will cost it roughly $100 million in 2018.

Trade concerns are among the factors that are rattling the U.S. stock market; the Standard & Poor's 500 stock index has tumbled 9.3 percent from its record high in September.

In the meantime, with costs rising, Scott has had to scramble to limit his company's expenses. When he visited Las Vegas this month for a trade show, only he and his wife and co-owner, Diane, went, rather than the half-dozen from his company who attended last year. It meant their booth wasn't fully staffed during the whole show.

Rob Martin, an economist at UBS, notes that U.S. tariffs are now at their highest levels since 1971. And back in the early '70s, trade constituted a much smaller portion of the economy. Now, import taxes are rising at a time when the U.S. has become far more integrated with the global economy, which means tariffs now tend to inflict heavier damage.

"No one has seen this phenomenon in the U.S.," Martin said.

Though Scott has absorbed his higher costs for now, he hopes to eventually pass some of them on to his customers, which include Shell Oil's convenience stores and Texas Roadhouse restaurants.

First, though, he wants to see how his larger competitors handle the higher costs.

"Little Howard McCray can't go out and raise prices 10 percent and lose all the market share that we've worked so hard to gain," Scott said.

Especially when his business, small as it is, is entwined in international trade. Like many companies, McCrary both benefits and suffers from globalization. Scott has worked to expand his business to Canada; 10 percent of his sales now come from that country. He felt relief when the U.S. agreed last month on an updated trade agreement with Canada and Mexico.

On the other hand, the company produces a commercial refrigerator that Scott says Chinese companies sell for less than the cost of his parts alone. He'd favor a tariff on that refrigerator.

Howard McCray buys its parts from distributors that acquire them from other manufacturers. If its American suppliers were to acquire their parts from China or some another country, Scott wouldn't always know about it — maybe not until an email arrived announcing a price hike to reflect new tariffs. Like a family shopping at a department store for clothes or toys imported from China, Scott didn't choose to acquire parts from overseas.

"The source of where their factories are is very hard for us to stay on top of," Scott says, standing before dozens of bins holding screws, wiring and electrical components. For many products, there aren't any alternative U.S. suppliers.

"If one moves (to China), they all move," says Bill Warren, his business partner.

Scott holds up a handful of Chinese-made shelf brackets dipped in chrome. One of his suppliers now charges 10 percent more for them because of the latest round of tariffs on Chinese imports. And the tariffs are set to rise to 25 percent on Jan. 1. Environmental regulations make it too expensive to manufacture them in the United States.

Scott decided to gamble a bit, and bought a year's supply of the brackets in August, when he first heard the tariffs might be imposed. That decision could save the company money if the tariffs increase as scheduled.

On the other hand, if the Trump administration reaches an agreement with Beijing before year's end and the tariffs come off, Scott will have bought too many. Yet he has no alternative.

"We are still buying Chinese," Scott says. "If there was an American manufacturer that made a shelf bracket, we would shift to that."