Researchers at City, University of London are developing new vibration-control devices based on Formula 1 technology so "needle-like" high-rise skyscrapers which still withstand high winds can be built

Current devices called tuned mass dampers (TMDs) are fitted in the top floors of tall buildings to act like heavyweight pendulums counteracting building movement caused by winds and earthquakes. But they weigh up to 1,000 tons and span five storeys in 100-storey buildings - adding millions to building costs and using up premium space in tight city centres.

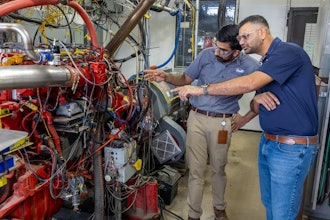

Recent research work published by Dr Agathoklis Giaralis (an expert in structural dynamics at City, University of London), and his colleagues, published in the November 2019 edition of the Engineering Structures journal (Optimal tuned mass damper inter design in wind-excited tall buildings for occupants' comfort serviceability, preferences and energy harvesting) found that lightweight and compact inerters, similar to those developed for the suspension systems of Formula 1 cars, can reduce the required weight of current TMDs by up to 70%.

Dr Giaralis said: "If we can achieve smaller, lighter TMDs, then we can build taller and thinner buildings without causing seasickness for occupants when it is windy. Such slender structures will require fewer materials and resources, and so will cost less and be more sustainable, while taking up less space and also being aesthetically more pleasing to the eye. In a city like London, where space is at a premium and land is expensive, the only real option is to go up, so this technology can be a game-changer."

Tests have shown that up to 30% less steel is needed in beams and columns of typical 20-storey steel building thanks to the new devices. Computer model analyses for an existing London building, the 48-storey Newington Butts in Elephant and Castle, Southwark, had shown that "floor acceleration" - the measure of occupants' comfort against seasickness - can be reduced by 30% with the newly proposed technology.

"This reduction in floor acceleration is significant," added Dr Giaralis. "It means the devices are also more effective in ensuring that buildings can withstand high winds and earthquakes. Even moderate winds can cause seasickness or dizziness to occupants and climate change suggests that stronger winds will become more frequent. The inerter-based vibration control technology we are testing is demonstrating that it can significantly reduce this risk with low up-front cost in new, even very slender, buildings and with small structural modifications in existing buildings." Dr Giaralis said there was a further advantage:

"As well as achieving reduced carbon emissions through requiring fewer materials, we can also harvest energy from wind-induced oscillations - I don't believe that we are able at the moment to have a building that is completely self-sustaining using this technology, but we can definitely harvest enough for powering wireless sensors used for inner building climate control."