Students sometimes pull an all-nighter to prepare for an exam. However, research has shown that sleep deprivation is bad for your memory. Now, University of Groningen neuroscientist Robbert Havekes discovered that what you learn while being sleep deprived is not necessarily lost, it is just difficult to recall. Together with his team, he has found a way to make this ‘hidden knowledge’ accessible again days after studying whilst sleep-deprived using optogenetic approaches, and the human-approved asthma drug roflumilast. These findings were published on December 27 in the journal Current Biology.

Havekes, associate professor of Neuroscience of Memory and Sleep at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands, and his team have extensively studied how sleep deprivation affects memory processes. ‘We previously focused on finding ways to support memory processes during a sleep deprivation episode’, says Havekes. However, in his latest study, his team examined whether amnesia as a result of sleep deprivation was a direct result of information loss, or merely caused by difficulties retrieving information. ‘Sleep deprivation undermines memory processes, but every student knows that an answer that eluded them during the exam might pop up hours afterwards. In that case, the information was, in fact, stored in the brain, but just difficult to retrieve.’

Hippocampus

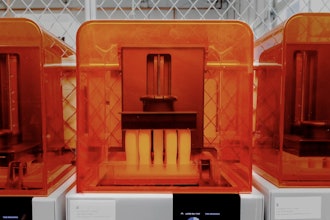

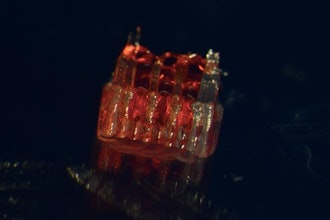

To address this question, Havekes and his team used an optogenetic approach: using genetic techniques, they caused a light-sensitive protein (channelrhodopsin) to be produced selectively in neurons that are activated during a learning experience. This made it possible to recall a specific experience by shining light on these cells. ‘In our sleep deprivation studies, we applied this approach to neurons in the hippocampus, the area in the brain where spatial information and factual knowledge are stored’, says Havekes.

First, the genetically engineered mice were given a spatial learning task in which they had to learn the location of individual objects, a process that heavily relies on neurons in the hippocampus. The mice then had to perform this same task days later, but this time with one object moved to a novel location. The mice that were deprived of sleep for a few hours before the first session failed to detect this spatial change, which suggests that they cannot recall the original object locations. ‘However, when we reintroduced them to the task after reactivating the hippocampal neurons that initially stored this information with light, they did successfully remember the original locations’, says Havekes. ‘This shows that the information was stored in the hippocampus during sleep deprivation, but couldn’t be retrieved without the stimulation.’

Memory problems

The molecular pathway set off during the reactivation is also targeted by the drug roflumilast, which is used by patients with asthma or COPD. Havekes: ‘When we gave mice that were trained while being sleep deprived roflumilast just before the second test, they remembered, exactly as happened with the direct stimulation of the neurons.’ As roflumilast is already clinically approved for use in humans, and is known to enter the brain, these findings open up avenues to test whether it can be applied to restore access to ‘lost’ memories in humans.

The discovery that more information is present in the brain than we previously anticipated, and that these ‘hidden’ memories can be made accessible again – at least in mice – opens up all kinds of exciting possibilities. ‘It might be possible to stimulate the memory accessibility in people with age-induced memory problems or early-stage Alzheimer’s disease with roflumilast’, says Havekes. ‘And maybe we could reactivate specific memories to make them permanently retrievable again, as we successfully did in mice.’ If a subject’s neurons are stimulated with the drug while they try and ‘relive’ a memory, or revise information for an exam, this information might be reconsolidated more firmly in the brain. ‘For now, this is all speculation of course, but time will tell.‘

At this time, Havekes is not directly involved in such studies in humans. ‘My interest lies in unravelling the molecular mechanisms that underlie all these processes’, he explains. ‘What makes memories accessible or inaccessible? How does roflumilast restore access to these ‘hidden’ memories? As always with science, by addressing one question you get many new questions for free.’