Vibrating tiny robots could revolutionize research.

Individual robots can work collectively as swarms to create major advances in everything from construction to surveillance, but microrobots’ small scale is ideal for drug delivery, disease diagnosis, and even surgeries.

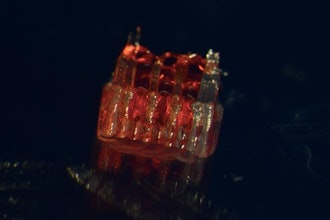

Despite their potential, microrobots’ size often means they have limited sensing, communication, motility, and computation abilities, but new research from the Georgia Institute of Technology enhances their ability to collaborate efficiently. The work offers a new system to control swarms of 300 3-millimeter microbristle robots’ (microbots) ability to aggregate and disperse controllably without onboard sensing.

The breakthrough is unique to Georgia Tech’s expertise in electric and computer engineering and robotics and its push for interdisciplinary collaborations.

“By collaborating with roboticists we were able to ‘close the gap’ between single robot design and swarm control,” said Azadeh Ansari, an assistant professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE). “So I guess the different elements were there, and we just made the connection.”

The researchers presented the work, “Controlling Collision-Induced Aggregations in a Swarm of Micro Bristle Robots,” in IEEE Transactions on Robotics.

The Challenges of Microbots

While larger robots can control movement through sensing the environment and wirelessly sending this data to each other, microbots do not have the capacity to carry the same sensors, communications, or power units. In this study, the researchers instead utilized inter-robot physical interactions to encourage robots to swarm.

“Microbots are too small to interpret and make decisions, but by using the collision between them and how they respond to frequency and the amplitude of global vibration actuation, we could influence how individual robots move and the collective behaviors of hundreds and thousands of these tiny robots,” said Zhijian Hao, an ECE Ph.D. student.

These behaviors, or motility characteristics, determine how microbots move linearly and the randomness in their rotation. By using vibration, the researchers could control these motility characteristics and perform motility-induced phase separation (MIPS). The researchers borrowed the concept from thermodynamics, when an agitated material can change phases from solid to gas to liquid. The researchers manipulated the level of vibration to influence the microbots to form clusters or disperse to create good spatial coverage.

To better understand these phase separations, they developed computational models and a live tracking system for the 300-robot swarm using computer vision. These enabled the researchers to analyze microrobots’ behavior and motion data that give rise to the swarm’s characteristics.

“This project is the first complete pipeline using this MIPS that can be generalized to different microbot swarms,” Hao said. “We hope people will find that using physical interactions is another new way to control the microbots, which initially was very difficult to do.”

Collaborating for Innovation

A Georgia Tech seed grant from the Institute for Robotics and Intelligent Machines (IRIM) and the Institute for Electronics and Nanotechnology enabled this high-risk research.

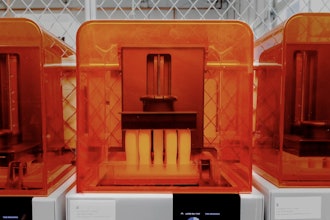

The success of the project can be attributed to the interdisciplinary nature of the research. While the ECE researchers had expertise in building microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) to fabricate technology such as computer chips or microbots, the robotics researchers brought modeling experience. Ansari first created microbristle bots in 2019 from 3D-printed polymers, which seeded the collaboration with IRIM Director and Professor Seth Hutchinson and Professor Magnus Egerstedt, now at University of California, Irvine, and their Ph.D. students Sid Mayya and Gennaro Notomista.

“We knew more about how to build micro devices and actuate them, and they knew more about the algorithms, modelings, and the closed-loop and open-loop control,” Ansari said. “So, it was very good interdisciplinary work because each group benefited from the new perspectives that the others brought to this.”