The idea of implantable sensors that continuously transmit information on vital values and concentrations of substances or drugs in the body has fascinated physicians and scientists for a long time. Such sensors enable the constant monitoring of disease progression and therapeutic success. However, until now implantable sensors have not been suitable to remain in the body permanently but had to be replaced after a few days or weeks. On the one hand, there is the problem of implant rejection because the body recognizes the sensor as a foreign object. On the other hand, the sensor's color which indicates concentration changes has been unstable so far and faded over time. Scientists at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) have developed a novel type of implantable sensor which can be operated in the body for several months. The sensor is based on color-stable gold nanoparticles that are modified with receptors for specific molecules. Embedded into an artificial polymeric tissue, the nanogold is implanted under the skin where it reports changes in drug concentrations by changing its color.

Implant reports information as an "invisible tattoo"

Professor Carsten Soennichsen's research group at JGU has been using gold nanoparticles as sensors to detect tiny amounts of proteins in microscopic flow cells for many years. Gold nanoparticles act as small antennas for light: They strongly absorb and scatter it and, therefore, appear colorful. They react to alterations in their surrounding by changing color. Soennichsen's team has exploited this concept for implanted medical sensing.

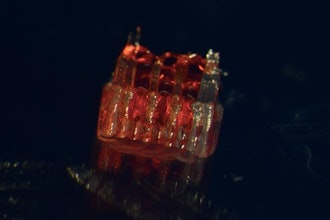

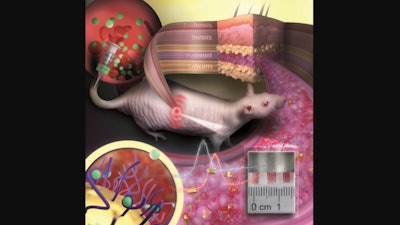

To prevent the tiny particles from swimming away or being degraded by immune cells, they are embedded in a porous hydrogel with a tissue-like consistency. Once implanted under the skin, small blood vessels and cells grow into the pores. The sensor is integrated in the tissue and is not rejected as a foreign body. "Our sensor is like an invisible tattoo, not much bigger than a penny and thinner than one millimeter," said Professor Carsten Soennichsen, head of the Nanobiotechnology Group at JGU. Since the gold nanoparticles are infrared, they are not visible to the eye. However, a special kind of measurement device can detect their color non-invasively through the skin.

In their study published in Nano Letters, the JGU researchers implanted their gold nanoparticle sensors under the skin of hairless rats. Color changes in these sensors were monitored following the administration of various doses of an antibiotic. The drug molecules are transported to the sensor via the bloodstream. By binding to specific receptors on the surface of the gold nanoparticles, they induce color change that is dependent on drug concentration. Thanks to the color-stable gold nanoparticles and the tissue-integrating hydrogel, the sensor was found to remain mechanically and optically stable over several months.

Huge potential of gold nanoparticles as long-lasting implantable medical sensors

"We are used to colored objects bleaching over time. Gold nanoparticles, however, do not bleach but keep their color permanently. As they can be easily coated with various different receptors, they are an ideal platform for implantable sensors," explained Dr. Katharina Kaefer, first author of the study.

The novel concept is generalizable and has the potential to extend the lifetime of implantable sensors. In future, gold nanoparticle-based implantable sensors could be used to observe concentrations of different biomarkers or drugs in the body simultaneously. Such sensors could find application in drug development, medical research, or personalized medicine, such as the management of chronic diseases.

Interdisciplinary team work brought success

Soennichsen had the idea of using gold nanoparticles as implanted sensors already in 2004 when he started his research in biophysical chemistry as a junior professor in Mainz. However, the project was not realized until ten years later in cooperation with Dr. Thies Schroeder and Dr. Katharina Kaefer, both scientists at JGU. Schroeder was experienced in biological research and laboratory animal science and had already completed several years of research work in the USA. Kaefer was looking for an exciting topic for her doctorate and was particularly interested in the complex and interdisciplinary nature of the project. Initial results led to a stipend awarded to Kaefer by the Max Planck Graduate Center (MPGC) as well as financial support from Stiftung Rheinland-Pfalz für Innovation. "Such a project requires many people with different scientific backgrounds. Step by step we were able to convince more and more people of our idea," said Soennichsen happily. Ultimately, it was interdisciplinary teamwork that resulted in the successful development of the first functional implanted sensor with gold nanoparticles.