A handful of the dozens of experimental COVID-19 vaccines in human testing have reached the last and biggest hurdle — looking for the needed proof that they really work as a U.S. advisory panel suggested Tuesday a way to ration the first limited doses once a vaccine wins approval.

AstraZeneca announced Monday its vaccine candidate has entered the final testing stage in the U.S. The Cambridge, England-based company said the study will involve up to 30,000 adults from various racial, ethnic and geographic groups.

Two other vaccine candidates began final testing this summer in tens of thousands of people in the U.S. One was created by the National Institutes of Health and manufactured by Moderna Inc., and the other developed by Pfizer Inc. and Germany’s BioNTech.

“To have just one vaccine enter the final stage of trials eight months after discovering a virus would be a remarkable achievement; to have three at that point with more on the way is extraordinary,” Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement.

NIH Director Francis Collins tweeted that his agency "is supporting several vaccine trials since more than one may be needed. We have all hands on deck."

AstraZeneca said development of the vaccine, known as AZD1222, is moving ahead globally with late-stage trials in the U.K., Brazil and South Africa. Further trials are planned in Japan and Russia. The potential vaccine was invented by the University of Oxford and an associated company, Vaccitech.

Meanwhile, a U.S. advisory panel released a draft plan Tuesday for how to ration the first doses of vaccine. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine proposed giving the first vaccine doses — initial supplies are expected to be limited to up to 15 million people — to high-risk health care workers and first responders.

Next, older residents of nursing homes and other crowded facilities and people of all ages with health conditions that put them at significant danger would be given priority. In following waves of vaccination, teachers, other school staff, workers in essential industries, and people living in homeless shelters, group homes, prisons and other facilities would get the shots.

Healthy children, young adults and everyone else would not get the first vaccinations, but would be able to get them once supplies increase.

The panel of experts described “a moral imperative” to lessen the heavy disease burden of COVID-19 on Blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans and Alaska Natives, and suggested state and local authorities could target vulnerable neighborhoods using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The National Academies will solicit public comments on the plan through Friday.

There’s a good reason so many COVID-19 vaccines are in development.

“The first vaccines that come out are probably not going to be the best vaccines,” Dr. Nicole Lurie, who helped lead pandemic planning under the Obama administration, said at a University of Minnesota vaccine symposium.

There’s no guarantee that any of the leading candidates will pan out — and the bar is higher than for COVID-19 treatments, because these vaccines will be given to healthy people. Final testing, experts stress, must be in large numbers of people to know if they’re safe enough for mass vaccinations.

They’re made in a wide variety of ways, each with pros and cons. One problem: Most of the leading candidates are being tested with two doses, which lengthens the time required to get an answer — and, if one works, to fully vaccinate people.

Another: They’re all shots. Vaccine experts are closely watching development of some nasal-spray alternatives that just might begin the first step of human testing later this year — late to the race, but possibly advantageous against a virus that sneaks into the airways.

For now, here’s a scorecard of vaccines that already have begun or are getting close to final-stage tests:

Genetic code vaccines

The Moderna and Pfizer candidates began Phase 3 testing in late July.

Neither uses the actual coronavirus. Instead, they’re made with the genetic code for the aptly named “spike” protein that coats the surface of the coronavirus. Inject the vaccine containing that code, called mRNA, and the body’s cells will make some harmless spike protein — just enough for the immune system to respond, priming it to react if it later encounters the real virus.

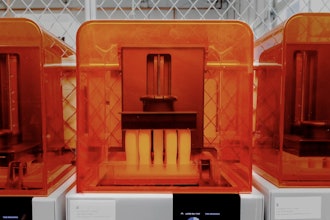

These mRNA vaccines are easier and faster to make than traditional vaccines, but it’s a new and unproven technology.

Trojan horse vaccines

Britain’s Oxford University and AstraZeneca are making what scientists call a “viral vector” vaccine but a good analogy is the Trojan horse. The shots are made with a harmless virus — a cold virus that normally infects chimpanzees — that carries the spike protein’s genetic material into the body. Once again, the body produces some spike protein and primes the immune system, but it, too, is a fairly new technology.

Two possible competitors are made with different human cold viruses.

Shots made by Johnson & Johnson began initial human studies in late July. The company plans to begin Phase 3 testing in September in as many as 60,000 people in the U.S. and elsewhere.

China’s government authorized emergency use of CanSino Biologics’ adenovirus shots in the military ahead of any final testing.

'Killed' vaccines

Making vaccines by growing a disease-causing virus and then killing it is a tried-and-true approach — it’s the way Jonas Salk’s famed polio shots were made. China has three so-called “inactivated” vaccine candidates against COVID-19 made this way.

Sinovac has final studies of its candidate underway in Brazil and Indonesia. Competitor SinoPharm has announced plans for final testing in some other countries.

Safely brewing and then killing the virus takes longer than newer technologies. But inactivated vaccines give the body a sneak peek at the germ itself rather than just that single spike protein.

Protein vaccines

Novavax makes “protein subunit” vaccines, growing harmless copies of the coronavirus spike protein in the laboratory and packaging them into virus-sized nanoparticles.

There are protein-based vaccines against other diseases, so it’s not as novel a technology as some of its competitors. But it only recently finished its first-step study; the U.S. government’s Operation Warp Speed aims for advanced testing later in the fall.