PFAS, or per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances, are a problem. Also called "forever chemicals," PFAS are commonly used in non-stick coatings, lubricants and fire-fighting foams, but they are turning up everywhere.

The chemical has been linked to everything from cancer to increased cholesterol to pregnancy problems.

They have seeped into water systems across the nation, and just this week, the FDA announced that it found "substantial levels" of PFAS in food; it was in everything from grocery store meats and seafood to an off-the-shelf chocolate cake. It's even in my wells.

So what are we doing about it? Not much. Some states have started suing manufacturers, but the nation seems crippled by the cleanup cost, which is estimated in the tens of billions of dollars.

However, researchers from the Flinders University Institute for NanoScale Science and Technology in Adelaide, Australia, have created a safe, environmentally friendly and low-cost way to remove PFAS from water — it turns out that Australia has quite the PFAS problem, too.

The researchers made an absorbent polymer from waste cooking oil and sulfur combined with powdered activated carbon.

PAC is a low-cost sorbent used to remove micropollutants from water. However, it creates a hazardous dust that is flammable and a respiration hazard. It can also cake, which blocks filters and membranes. The sulfur polymer support solves these problems.

Magnified view of the Powdered Activated Carbon polymer which bonds with water-borne PFAS, enabling it's removal from the environment.Flinders University

In initial tests, the polymer-carbon blend reduced the PFAS in water from 150 parts per trillion to less than 23 parts per trillion, well below the 70 ppt limit set by the EPA and other health organizations.

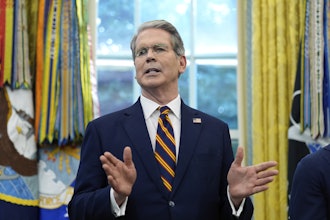

Flinders University PhD candidate Nicholas Lundquist (left) and Dr Justin Chalker (right) with a field sample of PFAS contaminated water.Flinders University

The research was recently published in ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering.

Next, the team plans to test the blend on a commercial scale to prove that it is capable of purifying thousands of gallons of water. They are also looking into ways to recycle the material and destroy the PFAS.