Just north of Emporia, one of Virginia's poorest cities, sits a 1,600-acre tract of weeds, wildflowers and the occasional wild turkey. Save for a few patches of trees and parcels of cotton, the site is virtually empty.

But it's heavy with expectations.

Officials have poured about $25 million into the Mid-Atlantic Advanced Manufacturing Center in the hope of attracting a factory filled with workers bringing home healthy paychecks, bolstering a region with high unemployment and few opportunities, but haven't succeeded so far.

In the past decade, the state has sunk more than $100 million into land acquisition and development at a handful of such megasites dotting Virginia's struggling rural south and southwest but has little to show for it, losing out to states offering better infrastructure and incentives.

A heavier focus on land acquisition rather developing the sites so plants can be operational within 18 months has put Virginia at a disadvantage as other Southern states welcome advanced manufacturing projects such as car and aerospace factories and pharmaceutical and fertilizer plants, top economic development officials and lawmakers say.

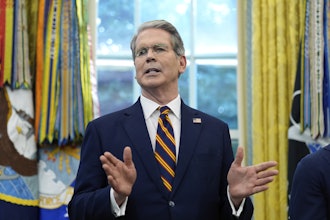

"We can make the first cut or two on a big project, but when we get down to the very end, ... we are limited in what we can offer in the commonwealth," said Republican Del. Chris Jones, chairman of the House Appropriations Committee.

Virginia also can't compete with other Southern states offering massive direct incentives, as state officials have balked at matching the big checks. South Carolina, for example, beat out Virginia for a Volvo plant after offering about $200 million in incentives.

John Boyd Jr., a New Jersey-based site selection consultant, said Virginia enjoys a good reputation as a business-friendly state but landing a major car manufacturing plant is unlikely because carmakers prefer to locate in other Southern states with an existing supply chain.

"Success breeds success in this industry," he said.

Affluent Northern Virginia — with a booming, diverse workforce and close proximity to the federal government — has excelled at luring new businesses. Amazon cited the area's plentiful tech workers when recently announcing it was building a new headquarters there.

Virginia officials say a key lesson from landing Amazon over states that offered three or four times as much cash is that incentives are only one factor companies consider when picking locations. Workforce development is key, too — one that Virginia has neglected when choosing sites in the past, Secretary of Finance Aubrey Layne said.

"Some of these sites, we could get them ready and I think they still have a very little chance of succeeding," Layne said.

Compounding the issue, the state doesn't know exactly what it has to offer companies. The online database of available sites, both for megasites and smaller locations, is missing critical information, like what kind of utility infrastructure is available, Virginia Economic Development Partnership President and CEO Stephen Moret said.

The development partnership is working on a detailed inventory of sites 25 acres and bigger. Until that study is done, Moret said, it's too soon to say whether public money has been spent on a site that will have to be written off.

"I truly don't know," he said.

That's raised some questions about whether spending on the megasites is worthwhile.

"This school of 'if we build it, they will come' on spec is risky business," said Greg LeRoy, executive director of the corporate subsidies watchdog group Good Jobs First.

The push to create megasites began in 2004, when several manufacturers were looking for locations in the Southeast, according to Tim Pfohl, grants director for Virginia's tobacco commission. The commission, an independent board created to use national tobacco settlement money to promote economic development in tobacco-dependent areas, allocated $100 million to buy land and bring in infrastructure.

Nearly all of that has been spent on eight sites in the state's south and southwest, and even more money has been sunk into the sites by other grants and local governments.

Former Gov. Gerald Baliles recently suggested in a speech to higher education officials that perhaps a better use for the commission's remaining money — which has funded projects far beyond just megasites — would be to funnel it instead into a trust fund for education.

But Moret said preparing sites is critical if the state wants to increase the number of advanced manufacturing jobs. He said Virginia needs more fully developed sites and a better-coordinated effort between local governments, the state and private businesses like Dominion Energy, the state's largest electric utility. Without that focus and commitment, he said, neighboring states are just more attractive to companies looking to build.

"We have to have prepared sites or we're going to lose," Moret said.

Gov. Ralph Northam recently proposed spending $20 million more to improve infrastructure at the state's megasites. Layne said the money, which has to be approved by the General Assembly, will be limited to the sites determined most likely to attract new businesses.

The director of economic development for Greensville County, home to the Mid-Atlantic Advanced Manufacturing Center, said it's hard to explain to people that developing megasites is a long process when they see millions going in and nothing coming out. Natalie Slate said the site has come close to landing major projects, including the Volvo manufacturing plant that instead chose South Carolina.

The Greensville site is even more attractive after a recent $2.2 million state grant to upgrade its sewage infrastructure, she said.

"We're ready," Slate said. "We're getting a lot more attention."