In 2003, Boeing launched a revolutionary new supply chain model in which it would subcontract to 30 Tier 1 companies worldwide. At the time, I wondered how Boeing could communicate and control 30 Tier 1 suppliers in different time zones, with different languages, and with different cultures. I wondered how they could maintain quality and deliveries in such a revolutionary scheme.

I wrote about this Boeing decision in 2010 because it was very risky to prioritize cost savings over the old way of manufacturing parts with U.S. vendors. Let's examine how it worked on two major projects, the 787 Dreamliner and the 737 MAX.

The 787's Problematic History

- June 2006: Boeing announces that bubbles are found in the composites on a prototype section.

- April 2007: Sales exceed 500 planes and Boeing looks to accelerate production.

- June 2007: They find that the cockpit section is out of line with the fuselage.

- June 2007: An industry-wide shortage of fasteners causes production problems.

- October 2007: Boeing delays first deliveries by six months.

- October 2007: Michael Bair, GM of the 787 program, is replaced, saying suppliers of major components of the 787 have fallen short of Boeing's expectations.

- December 2007: CEO Scott Carson says there will be no further delays in the 787 program, and then a three-month delay is announced in April.

- September 2008: Installation of improper fasteners and a union strike pushes deliveries into the first quarter of 2010.

- June 2009: Designers find that reinforcements are needed where the wing joins the fuselage, which will further delay the first deliveries.

- August 2009: Boeing discovers microscopic wrinkles in the fuselage skin and has to install a composite patch over the area.

- 2009: Boeing orders Italian supplier Alenia Aeronautica to halt production of fuselage sections.

- 2009: Boeing announces a $2.5 billion charge to third-quarter earnings and pushes deliveries to the fourth quarter of 2010, two years later than the original schedule.

- 2009: Boeing decides to build a non-union plant to build the 787 in South Carolina.

- 2012: 31 of the first 787s had missing O-rings, lock wires and fastener retaining rings.

- 2014: Lithium-ion battery overheating problem grounds the 787 fleet.

- 2020: Shim issues on the fuselage and out-of-tolerance issues with the inner mold line.

- 2021: Boeing decides to close the 787 unionized plant in Washington and keep the non-union plant in South Carolina.

- 2024: A new investigation starts after Boeing admits it might have skipped required inspections involving 787 wings.

The 787 Dreamliner ended up three years late and billions over budget.

The 737 Max's Problematic History

- 2011: Boeing's CEO McNerney decides to put new engines on the original 737 rather than build a completely new plane.

- 2017: The first 737 Max ships to Southwest Airlines on August 20.

- 2018: A Lions Air 737 Max crashes after leaving from Jakarta, Indonesia, killing 189 people. Boeing convinces the FAA to keep planes flying and issues a statement that "the 737 Max is as safe as any airplane that has flown the skies."

- 2019: An Ethiopian Airlines Max crashes minutes after takeoff, killing all 157 people on board.

- 2019: The plane is grounded and the FAA concludes that a design flaw in the maneuvering characteristics augmentation system (MCAS) caused both crashes.

- 2019: Ed Pearson, a senior manager at the Boeing 737 factory, testified to Congress that there was evidence that the 737 Max was having production quality issues, faulty hardware and more than a dozen safety issues. He recommended a production halt before the first crash but was overruled by his boss.

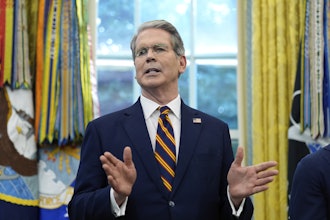

- 2020: Dave Calhoun is hired as the new chief executive to manage the 737 Max problems. He was from General Electric and had no engineering experience.

- 2023: In a speech to investors, Calhoun said Boeing "has added rigor around our quality processes" and is making progress with its quality problems.

- 2024: Ten weeks after Calhoun's statement, an Alaska Air 737 Max experiences a plug door blowout from the fuselage while in flight.

- 2024: The FAA grounds the 737 Max again.

- 2024: The FAA audits Renton and Spirit Systems plants, and Boeing fails 33 of 89 product audits. The audits find problems with manufacturing process control, parts handling and storage, and product control. President Stan Deal announces additional inspections and a review of Spirit AeroSystems' build processes.

- March 2024: Boeing's airline customers, including United, Southwest, Alaska, and American, demanded to meet Boeing's board on lack of progress. Boeing's board then asked CEO Calhoun, Chairman Larry Kellner, and Commercial Airplane President Stan Deal all to resign. It became obvious to Boeing's airline customers that the financial approach to their quality and reduction problems was not going to cut it.

When Boeing's Problems Began

Many critics believe that Boeing's problems began many years before the 787 and 737 issues. In 1997, Boeing acquired archrival McDonnell Douglas, which was known for cost-cutting and upgrading older models. Boeing's board convinced former McDonnell executive Harry Stonecipher to replace Philip Condit as CEO. Stonecipher was a General Electric alum who immediately set out to change Boeing's culture, proclaiming, "When people say I changed the culture of Boeing, that was the intent, so that it is run like a business rather than a great engineering firm." This prophetic statement would lead to a total change in the direction of the Boeing Company.

Stonecipher was true to his word and did not invest in new models. Instead, he elected to maximize profits from older models and use the cash for stock buybacks. Stonecipher also decided to sell its Wichita fuselage division to Spirit AeroSystems for $900 million. So began the cultural shift that put profits and shipments ahead of quality and safety, placing the company, the airline customers, and the passengers at risk.

Stonecipher resigned after two years, and he was replaced by another GE executive in 2005, Jim McNerney, who had no engineering and limited aerospace experience. Rather than designing a new aircraft to replace the 737, McNerney opted to upgrade the old model. The problem with putting new engines on the old model was that engines were too large for the airplane, causing the plane's nose to rise with the potential to stall. Boeing used an MCAS sensor to compensate, but MCAS didn't fix the problem. It was a workaround for a fundamental design flaw that allowed the pilots to compensate for pitch-up of the nose. It became a fatal mistake when Boeing decided to tell their customers that they wouldn't have to retrain pilots or upgrade its training manuals—which were factors in both 737 Max crashes.

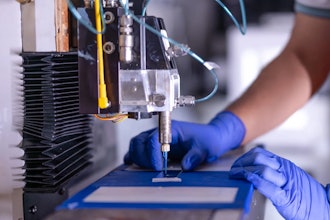

Boeing's problems date back twenty years to the company's 2003 supplier policy. At the time, it was a revolutionary approach to cost savings versus control of production. If it had worked, Boeing would have pioneered a new manufacturing model for globalized manufacturing. But it didn't work very well for either the 787 or the 737 MAX, especially in terms of controlling quality or production.

Quality vs. Shipments

In the 1990s, Boeing adopted the Lean Six Sigma process to reduce costs and create a more efficient manufacturing process. If they had used the lean process correctly, their production and quality problems should have triggered root cause problem solving that was focused on long-term improvements. More importantly, when quality problems with safety implications emerged, the company should have stopped the production line to address defects. Instead, they used "traveled work" which just pushed the problems down the line. Traveled work refers to issues that are "delayed and/or completed in a factory location other than what was originally planned." The company chose not to adhere to these lean principles.

Since the beginning of Boeing's quality problems, the company has struggled with the issue of quality versus shipments. Because they began to lose a lot of money after the 737 Max crashes, the pressure was on to get into the black, and shipments became more important.

Financialization Handcuffs the Company

From the first crash of the 737 Max in 2017, the financially driven management team seemed frozen in the headlights and unable to grasp the extent of their engineering and production problems. It was all driven by financially-minded managers who did not have engineering or aerospace experience. Because Boeing was losing money, they thought they were making the right decisions.

In their culture, the schedule was king and moving airplanes through the factory was more important than quality or safety. It finally caught up to management after the plug door incident. In hindsight, they would have been financially better off if they had shut down the 737 Max line after the first crash until all of the quality, engineering, and supplier problems were totally resolved.

The cultural shift from engineering and quality to a company focused on profit and shareholder value led to Boeing's worst financial situation in 100 years. Since 2019, Boeing has lost more than $32 billion, mostly due to the 737 Max problems. Ironically, they have lost more money than it would have taken to completely redesign the 737 into a true competitor to the Airbus A320neo, which has benefitted from Boeing's problems.

Public Relations Statements

After the 737 Max crash, Boeing executives continued to issue public relations statements on how safe Boeing's airplanes were and how rigorous their quality programs were, even though the evidence showed that quality, supplier, and production problems were ongoing. Management seemed torn between focusing on the production problems and increasing shipments right up until the January 2024 plug-door blowout.

After the incident, the FAA conducted 89 product audits, and Boeing failed 33 of them, with a total of 97 instances of noncompliance. After the audit, the FAA gave Boeing 90 days to come up with a plan to improve quality and safety.

Boeing released their turnaround plan to improve safety and quality on May 31, 2024. CEO Calhoun said in a statement that "it is this continuous learning and improvement process that our industry has made commercial aviation the safest mode of transportation." This statement rings hollow when you look at Boeing's 787 and 737 projects and Boeing's safety record. According to the Aviation Safety Network, since 1975, there have been 149 fatal accidents with Boeing airplanes, but only 24 were on Airbus airplanes.

Boeing's board waited far too long to make management changes and failed to take aggressive action to solve the production quality and safety issues. During all of these problems, they paid CEO Calhoun $32.8 million in 2023, which seems very excessive for someone who was in charge during the company's continued quality problems and financial losses.

Boeing announced plans to buy back key supplier Spirit AeroSystems for $4.7 billion this week. Perhaps it is time to abandon the idea of global suppliers and return to U.S. vendors it can own and control.

The financialization of the company and loss of supplier and quality control ruined the flagship American company that once built the most innovative airliners in the world. Airbus is a state-owned company, and Boeing's problems beg the question of whether a publicly traded and shareholder-owned company with financially trained managers can address Boeing's quality and production problems or even compete with Airbus in the future.

In a few words, Boeing bet the farm and has almost lost the farm.

Michael Collins is the author of "Dismantling the American Dream: How Multinational Corporations Undermine American Prosperity." He can be reached at mpcmgt.net.