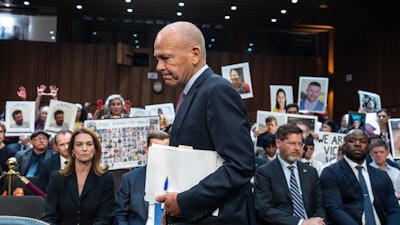

Boeing CEO David Calhoun defended the company’s safety record during a contentious Senate hearing Tuesday, while lawmakers accused him of placing profits over safety, failing to protect whistleblowers, and even getting paid too much.

Relatives of people who died in two crashes of Boeing 737 Max jetliners were in the room, some holding photos of their loved ones, to remind the CEO of the stakes. Calhoun began his remarks by standing, turning to face the families, and apologizing “for the grief that we have caused,” and vowing to focus on safety.

Calhoun's appearance was the first before Congress by any high-ranking Boeing official since a panel blew out of a 737 Max during an Alaska Airlines flight in January. No one was seriously injured in the incident, but it raised fresh concerns about the company’s best-selling commercial aircraft.

The tone of the hearing before the Senate investigations subcommittee was set hours earlier, when the panel released a 204-page report with new allegations from a whistleblower who said he worries that defective parts could be going into 737s. The whistleblower is the latest in a string of current and former Boeing employees to raise concerns about the company's manufacturing processes, which federal officials are investigating.

Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., placed the blame squarely on Calhoun, saying that the man who became CEO in January 2020 had been too focused on the bottom line.

Hawley repeatedly mentioned Calhoun's compensation for last year, valued at $32.8 million, and asked the CEO why he hasn't resigned.

Senators pressed Calhoun about accusations that Boeing managers retaliated against employees who reported safety concerns. They asked the CEO if he ever spoke with any whistleblowers. He replied that he had not, but agreed it would be a good idea.

The latest whistleblower, Sam Mohawk, a quality assurance investigator at Boeing's 737 assembly plant near Seattle, told the subcommittee that “nonconforming” parts — ones that could be defective or aren’t properly documented — could be winding up in 737 Max jets.

Potentially more troubling for the company, Mohawk charged that Boeing hid evidence after the Federal Aviation Administration told the company it planned to inspect the plant in June 2023.

The parts were later moved back or lost, Mohawk said. They included rudders, wing flaps and other parts that are crucial in controlling a plane.

A Boeing spokesperson said the company got the subcommittee report late Monday night and was reviewing the claims.

The FAA said it would “thoroughly investigate” the allegations. A spokesperson said the agency has received more reports of safety concerns from Boeing employees since the Jan. 5 blowout on the Alaska Airlines Max.

The 737 Max has a troubled history. After Max jets crashed in 2018 in Indonesia and 2019 in Ethiopia, killing 346 people, the FAA and other regulators grounded the aircraft worldwide for more than a year and a half. The Justice Department is considering whether to prosecute Boeing for violating terms of a settlement it reached with the company in 2021 over allegations that it misled regulators who approved the plane.

Mohawk told the Senate subcommittee that the number of unacceptable parts has exploded since production of the Max resumed following the crashes. He said the increase led supervisors to tell him and other workers to “cancel” records that indicated the parts were not suitable to be installed on planes.

The FAA briefly grounded some Max planes again after January’s mid-air blowout of a plug covering an emergency exit on the Alaska Airlines plane. The agency and the National Transportation Safety Board opened separate investigations of Boeing that are continuing.

Calhoun said Boeing has responded to the Alaska accident by slowing production, encouraging employees to report safety concerns, stopping assembly lines for a day to let workers talk about safety, and appointing a retired Navy admiral to lead a quality review. Late last month, Boeing delivered an improvement plan ordered by the FAA.

Calhoun defended the company’s safety culture while acknowledging that it “is far from perfect.”

The drumbeat of bad news for Boeing has continued in the past week. The FAA said it was investigating how falsely documented titanium parts got into Boeing's supply chain, the company disclosed that fasteners were incorrectly installed on the fuselages of some jets, and federal officials examined “substantial” damage to a Southwest Airlines 737 Max after an unusual mid-flight control issue.

Howard McKenzie, Boeing's chief engineer, said during the hearing that the issue affecting the Southwest plane — which he did not describe in detail — was limited to that plane.

Blumenthal first asked Calhoun to appear before the Senate subcommittee after another whistleblower, a Boeing quality engineer, claimed that manufacturing mistakes were raising safety risks on two of the biggest Boeing planes, the 787 Dreamliner and the 777. He said the company needed to explain why the public should be confident about Boeing’s work.

Boeing pushed back against the whistleblower's claims, saying that extensive testing and inspections showed none of the problems that the engineer had predicted.

The Justice Department determined last month that Boeing violated a 2021 settlement that shielded the company from prosecution for fraud for allegedly misleading regulators who approved the 737 Max. A top department official said Boeing failed to make changes to detect and prevent future violations of anti-fraud laws.

Prosecutors have until July 7 to decide what to do next. Blumenthal said there is “mounting evidence” that the company should be prosecuted.

Families of the victims of the Max crashes have pushed the Justice Department repeatedly to charge the company and individual executives. They want a federal judge in Texas to throw out the 2021 deferred-prosecution agreement or DPA — essentially a plea deal — that allowed Boeing to avoid being tried for fraud in connection with the Max.