A team mapping radio waves in the universe has discovered something unusual that releases a giant burst of energy three times an hour, and it’s unlike anything astronomers have seen before.

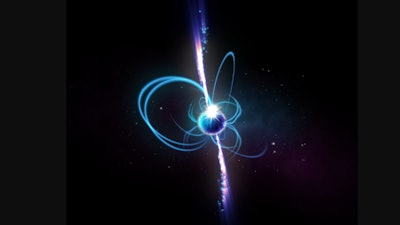

The team who discovered it think it could be a neutron star or a white dwarf — collapsed cores of stars — with an ultra-powerful magnetic field.

Spinning around in space, the strange object sends out a beam of radiation that crosses our line of sight, and for a minute in every twenty, is one of the brightest radio sources in the sky.

Astrophysicist Dr. Natasha Hurley-Walker, from the Curtin University node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, led the team that made the discovery.

“This object was appearing and disappearing over a few hours during our observations,” she said. “That was completely unexpected. It was kind of spooky for an astronomer because there’s nothing known in the sky that does that. And it’s really quite close to us — about 4,000 light years away. It’s in our galactic backyard.”

The object was discovered by Curtin University Honors student Tyrone O'Doherty using the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) telescope in outback Western Australia and a new technique he developed.

“It’s exciting that the source I identified last year has turned out to be such a peculiar object,” said O’Doherty, who is now studying for a PhD at Curtin. “The MWA’s wide field of view and extreme sensitivity are perfect for surveying the entire sky and detecting the unexpected.”

Objects that turn on and off in the universe aren’t new to astronomers — they call them "transients."

ICRAR-Curtin astrophysicist and co-author Dr. Gemma Anderson said that “when studying transients, you’re watching the death of a massive star or the activity of the remnants it leaves behind.”

"Slow transients" — like supernovae — might appear over the course of a few days and disappear after a few months.

"Fast transients" — like a type of neutron star called a pulsar — flash on and off within milliseconds or seconds.

But Dr. Anderson said finding something that turned on for a minute was really weird.

The Milky Way as viewed from Earth. The star icon shows the position of the mysterious repeating transient.Dr. Natasha Hurley-Walker (ICRAR/Curtin)

The Milky Way as viewed from Earth. The star icon shows the position of the mysterious repeating transient.Dr. Natasha Hurley-Walker (ICRAR/Curtin)

Dr. Hurley-Walker said the observations match a predicted astrophysical object called an "ultra-long period magnetar."

“It’s a type of slowly spinning neutron star that has been predicted to exist theoretically,” she said. “But nobody expected to directly detect one like this because we didn’t expect them to be so bright. Somehow, it’s converting magnetic energy to radio waves much more effectively than anything we’ve seen before.”

Hurley-Walker is now monitoring the object with the MWA to see if it switches back on.

“If it does, there are telescopes across the Southern Hemisphere and even in orbit that can point straight to it,” she said.

Hurley-Walker plans to search for more of these unusual objects in the vast archives of the MWA.

“More detections will tell astronomers whether this was a rare one-off event or a vast new population we'd never noticed before," she said.

MWA Director Professor Steven Tingay said the telescope is a precursor instrument for the Square Kilometre Array — a global initiative to build the world’s largest radio telescopes in Western Australia and South Africa.

“Key to finding this object, and studying its detailed properties, is the fact that we have been able to collect and store all the data the MWA produces for almost the last decade at the Pawsey Research Supercomputing Centre. Being able to look back through such a massive dataset when you find an object is pretty unique in astronomy,” he said. “There are, no doubt, many more gems to be discovered by the MWA and the SKA in coming years.”