TUCSON, Ariz. (AP) — Natural underground caverns on the moon could be used to store frozen samples of Earth’s species in order to protect biodiversity in the event of global catastrophe, according to a University of Arizona scientist and his students.

Jekan Thanga, a professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering, and five of his students presented a paper earlier this month on the concept during the international IEEE Aerospace Conference, which was held virtually this year, the Arizona Daily Star reported.

Thanga said the underground biological repository would serve as a backup copy of frozen seeds, spores, sperm and egg samples from most Earth species. The specimens would be kept safe inside the caves carved by molten lava hundreds of feet below the surface of the moon.

The caves, some large enough to hold a 30-story building, can be reached by rocket from Earth in four to five days and provide an environment essentially undisturbed for the past 3 to 4 billion years, scientists said.

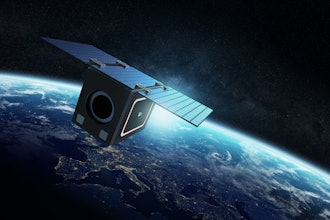

University doctoral candidate Álvaro Díaz-Flores Caminero and undergraduate student Claire Pedersen were the lead authors of the paper. They said the idea came from the biblical story of Noah's Ark, but instead of two of every animal the lunar ark would store 50 samples from each of the chosen species in a high-tech archive manned by robots and powered with solar panels. The group has been researching ideas amid global catastrophe for at least seven years.

“There’s nothing like that on planet Earth. There’s nothing as secure,” Thanga said, adding that it serves as “an insurance policy” in the event of global catastrophe.

Thanga estimates that it could take as little as five years and 15 space launches to create the repository.

Thanga also said it would be similar to that of the Svalbard Seed Bank, an existing repository in Norway that holds hundreds of thousands of plant samples. Instead, the one on the moon would hold as many as 1 million different seed packets.

The group hopes to send 6.7 million species to the moon, representing up to 90% of all known plants and animals, minus those that cannot be cryogenically preserved, he said. It is unclear what will happen to the samples once on the moon.

“We want to save it for a time when we have the technology to (re)deploy it,” he said. “Because once it’s lost it’s lost forever. There’s no way of getting it back.”

So far, work on the idea has been funded through a grant by NASA. The group has announced plans to release more details as they conduct more research, including how the samples might react to long-term storage in microgravity.

Díaz-Flores Caminero, a doctoral student who co-wrote the first paper on the concept, welcomes the challenge. “Multidisciplinary projects are hard due to their complexity. But I think the same complexity is what makes them beautiful,” he said.