The modules that the major space agencies plan to erect on the Moon could incorporate an element contributed by the human colonizers themselves: the urea in their pee. European researchers have found that it could be used as a plasticizer in the concrete of the structures.

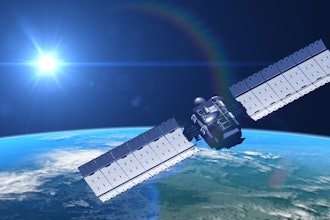

NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and its Chinese counterpart plan to build moon bases in the coming decades, as part of a broader space exploration plan that will take humans to more distant destinations, such as Mars.

However, the colonization of the Moon poses problems such as high levels of radiation, extreme temperatures, meteorite bombardment and a logistical issue: how to get construction materials there, although it may not be necessary.

Transporting about 0.45 kg from the Earth to space costs about $10,000, which means that building a complete module on our satellite in this way would be very expensive. This is the reason why space agencies are thinking of using raw materials from the moon's surface, or even those that astronauts themselves can provide, such as their urine.

Scientists from Norway, Spain, the Netherlands and Italy, in cooperation with ESA, have conducted several experiments to verify the potential of urine urea as a plasticizer, an additive that can be incorporated into concrete to soften the initial mixture and make it more pliable before it hardens. Details are published in the Journal of Cleaner Production.

"To make the geopolymer concrete that will be used on the moon, the idea is to use what is there: regolith (loose material from the moon's surface) and the water from the ice present in some areas," explains one of the authors, Ramón Pamies, a professor at the Polytechnic University of Cartagena (Murcia), where various analyses of the samples have been carried out using X-ray diffraction.

"But moreover," he adds, "with this study we have seen that a waste product, such as the urine of the personnel who occupy the moon bases, could also be used. The two main components of this body fluid are water and urea, a molecule that allows the hydrogen bonds to be broken and, therefore, reduces the viscosities of many aqueous mixtures."

Using a material developed by ESA, which is similar to moon regolith, together with urea and various plasticizers, the researchers, using a 3D printer, have manufactured various 'mud' cylinders and compared the results.

The experiments, carried out at Østfold University College (Norway), revealed that the samples carrying urea supported heavy weights and remained almost stable in shape. Once heated to 80°C, their resistance was also tested and even increased after eight freeze-thaw cycles like those on the Moon.

"We have not yet investigated how the urea would be extracted from the urine, as we are assessing whether this would really be necessary, because perhaps its other components could also be used to form the geopolymer concrete," says one of the researchers from the Norwegian university, Anna-Lena Kjøniksen, who adds: "The actual water in the urine could be used for the mixture, together with that which can be obtained on the Moon, or a combination of both."

The scientists stress the need for further testing to find the best building material for the moon bases, where it can be mass-produced using 3D printers.