Federal investigators say some safety inspectors who helped set pilot-training standards for the Boeing 737 Max were unqualified and the Federal Aviation Administration seemed to mislead Congress about their competency.

The FAA disputed part of the investigators' conclusions on Tuesday. The agency said all the inspectors who evaluated the Max were fully qualified for the work they did, and it stood by its statements to Congress.

The standoff between investigators and the FAA stems from a whistleblower complaint that was investigated by the U.S. Office of Special Counsel.

The special counsel's disclosures are another setback for the FAA, which is already under scrutiny for its certification of the 737 Max. According to published reports, senior FAA officials did not understand a key flight-control system that was later implicated in two crashes that killed 346 people.

The FAA determined that 16 of 22 inspectors in Seattle and Long Beach, California, had not finished their formal training, and of the 16, 11 did not hold a flight-instructor license, a requirement for the job. But, the FAA told a Senate committee this spring, they worked on other planes and none of the unqualified inspectors helped write training standards for the Max.

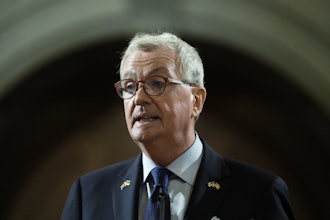

The special counsel said that was not true, based on information from the whistleblower and other evidence. Special Counsel Henry Kerner said it is likely that some Max inspectors were neither qualified to certify other pilots to fly nor to recommend how pilots should be trained for procedures and maneuvers on the plane.

In letters to President Donald Trump and key lawmakers, Kerner added that the FAA's answers to Congress about the matter "appear to have been misleading."

"The FAA's failure to ensure safety inspector competency for these aircraft puts the flying public at risk," Kerner said.

In response, the FAA said in a statement, "All of the Aviation Safety Inspectors who participated in the evaluation of the Boeing 737 MAX were fully qualified for those activities."

Then-acting FAA Administrator Daniel Elwell said in May that the whistleblower's complaint dealt with training requirements for inspectors on a different plane.

The Max remains grounded since mid-March, not long after the crash of a Max operated Ethiopian Airlines shortly after takeoff from Addis Ababa. That followed the October 2018 crash of a Lion Air Max off the coast of Indonesia.

Boeing is nearing completion of changes that it hopes will persuade regulators to let the plane fly again, and pilot training has emerged as a key issue.

Some safety advocates and relatives of passengers killed in the crashes demand that pilots be trained on flight simulators before the plane is put back in service — a requirement that would delay the plane's return by weeks or months.

Boeing believes that training on the updated flight-control system can be done on tablet computers and FAA technical advisers agree, although the agency has not made a final decision.